When I painted Femme-Maison in the 1940s, a figure made of half a woman and half a house, it was said that this work was typical of a female artist. I’m sorry but I do not know what “typical of a female artist” is supposed to mean. To all appearances, this woman is beautiful, however she does not realize the effect she has upon us. She doesn’t realize she’s half naked nor that she’s hiding. She’s in complete contradiction with herself because, whereas she thinks she’s hiding, she’s in fact revealing herself — Louise Bourgeois

(La Wander’s Note: On one of my final days in my neighborhood, I explored some places I hadn’t seen before. One of them was the the outstanding Women House exposition at Monnaie de Paris. Here’s a little slideshow of some highlights from the exposition that I wanted to share with you — I took all photos unless otherwise indicated!)

In 1972, Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago, co-founders of the California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Program, organized a collaborative art exhibition in Los Angeles that was made up of 17 rooms in an abandoned Victorian mansion that were transformed into art installations by 25 female artists (primarily students). The project, which took two months to construct, was about teaching the artists work skills but also to help them challenge the limiting expectations of womanhood. The women not only created the art but they renovated the mansion themselves (with limited outside help). Over the course of the project, “The age-old female activity of homemaking was taken to fantasy proportions. Womanhouse became the repository of the daydreams women have as they wash, bake, cook, sew, clean and iron their lives away” (Womanhouse Catalog Essay). The finished exhibition ran from January 30 – February 28, 1972.

Historically, of course, women have been relegated to (even imprisoned by) the domestic space — the private — while the public has been possessed by men. In the second wave of feminism in the 1960s/70s, “The Private is Political” was a sort of rallying cry of the movement. But how does that concept translate to today?

In the exposition Women House, art is used as a way to link female gender identity with a domestic space. In the eight chapters of the show, spanning 16 rooms plus an Introduction, the women artists confront and question the stereotypes and limitations imposed upon women by transforming the traditionally female space into one of creativity. The end result both demolishes and reclaims (or perhaps more specifically redefines) that traditional space. In my eyes, as I experienced the installations, this potentially brings women — both as artists and as viewers — to a more authentic understanding of self in the context of a larger world.

In the process, much like the 1970s mantra proclaims, the private becomes both public and political.

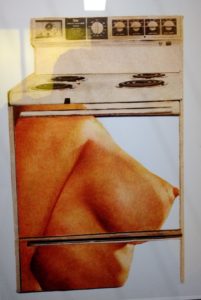

Chapter 1, Desperate Housewives: Many of the artists in this section reveal the contrast between the fantasy of home life with the monotonous reality of life for women who are confined to the home. A lot of the artists used irony or humor to challenge the (typically middle-class) stereotypes of life as a housewife.

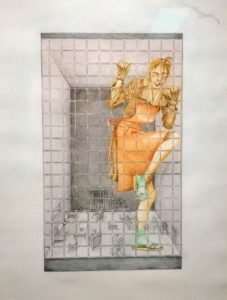

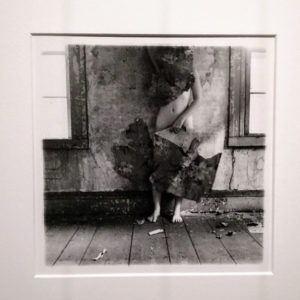

Chapter 2, Home is Where it Hurts: Many of the images in this section focused on a sense of entrapment — both physical and psychological — within spaces. The images conjured up feelings of isolation and desperation as the women attempted (or at the very least, considered) ways to emancipation. The juxtaposition of powerlessness with (oftentimes untapped) strength was sublime. One interesting video installment by Monica Bonvicini, had the artist pounding a wall with a sledgehammer. (Who can’t relate to that?)

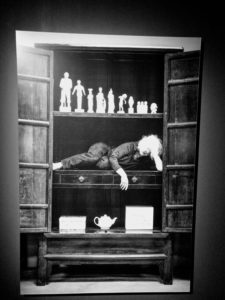

Chapter 3, A Room of One’s Own: This section takes its name from one of Virginia Woolf’s most-important works. In this piece of non fiction Woolf famously declares: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” This section considers the house as a place for inspiration, discovery, and reflection. Rather than be a place of confinement, in these works one’s personal space becomes a refuge. In many of the images we see women finding liberation, solitude, and sanctuary in their homes.

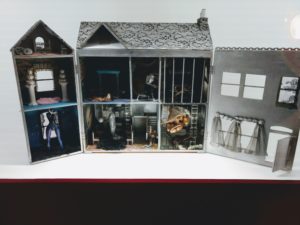

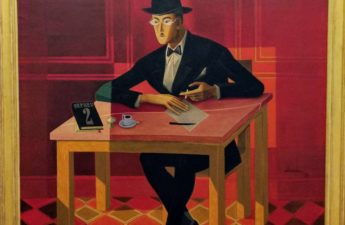

Chapter 4, Doll’s House: Coincidentally, a friend and I saw Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House a few years ago and felt that the production fell flat because it was interpreting the play too literally rather than thinking about it in the context of the modern era. But of course we both agreed that the text of the play is still relevant. In fact, one quote from the play on the walls of Women House reminded me how relevant a play that was written in 1879 still is: “Helmer: ‘First and foremost you’re a spouse and a mother.’ Nora: ‘I don’t believe this anymore. I believe that, first and foremost, I’m a human being, just as you are.'” Today, no matter how much progress we’ve made (whether as individuals or as a society), how much of a woman’s primary identity is still tied to an expectation that she is first a wife and mother? How much of her own identity is lost in the process? Taking the title of Ibsen’s play and spinning it almost 150 years later, the artists in this section have created miniature portrayals of domestic life. Interesting how the reality of domesticity can be so different from the fantasies we create as children playing house. One piece was a chess board that used domestic household items as its pieces. Another was a series of photographs of a doll’s house with a housewife figure put in places in the house where specific duties would be designated for her.

Chapter 5, Marks: The Women House brochure states that “the artworks in this section speak of absence: that of a body or that of a place.” The works in these rooms use artifacts to create a memory of a place. For me, seeing these larger installations was a bit ghostlike, though not in an eerie way, more in a living spirt sort of way. I’m not sure the photos convey this feeling (these were all fairly large installations using various textures which is hard to capture in a photo) but hopefully you’ll get at least a drop of a sense of them. I think that overall this was the most interesting room in the exhibition.

Chapter 6, Construction as Self-Construction: This section again considers the importance of a woman having access to a literal space, both to create and to display one’s work, as well as the symbolic space of recognition. (I didn’t get any photos of the two artists’ work — sorry!) Thinking back to Virginia Woolf, the notion of personal space is imperative. We are defined by our space yet, for many women, the space of our existence is often oppressive or confining. Constructing a space for oneself is a form of liberation and empowerment.

Chapter 7, Mobile Homes: This section presents “alternative lifestyles” through shelters that inspire a nomadic existence. Especially thought-provoking were the photographs by South African artist Sue Williamson that confront power and exile. I also loved the mini mobile-home that was a one-person hot tub (basically my life’s dream).

Chapter 8, Femmes-maisons: In this section, artists examine the female body in relation to the architecture of the house. In Louise Bourgeois’s “Femmes-maisons” the artist shows how the home — the domestic — consumes a woman, isolating and dehumanizing her. However many of the works in this section also highlight the female body as mother, — the giver, protector, and nurturer of life, even in the context of the stifling home, such as the work from Bourgeois’s “Spider” series.

Wow — looks like an amazing exhibit!

Oh, I’m so glad you saw this! You would have loved it. (I’m tossing all of the brochures I’m getting to lighten up my load, but I’m keeping the one from this — I’ll show you in the Spring!)