The tip of my mother’s walking stick hits the cobblestones in a hushed rhythm: tap, step, tap, step, tap, step, tap. We’ve been walking all day, up and down through the jungle of streets in Lisbon, and she is getting tired. But like a true flâneuse, my fearless mother powers forward.

“We’re almost there,” I say, stopping to check my phone to make sure that I haven’t accidentally led us to Belém. “About ten more minutes.”

“You said that about twenty minutes ago.” She pauses for a quick rest on a low wall.

Today we aren’t carelessly wandering; we have a goal in mind. We are searching for the house of one of Portugal’s most-treasured writers, Fernando Pessoa. It is, to say the least, a bit off the beaten path.

Fernando Pessoa, you say? Haven’t read him? That’s okay. Neither had I until one of my French friends recommended I read The Book of Disquiet in preparation for my trip to Portugal.

“He’s like your brother,” JJ said. “He is a solitary wanderer, just like you.”

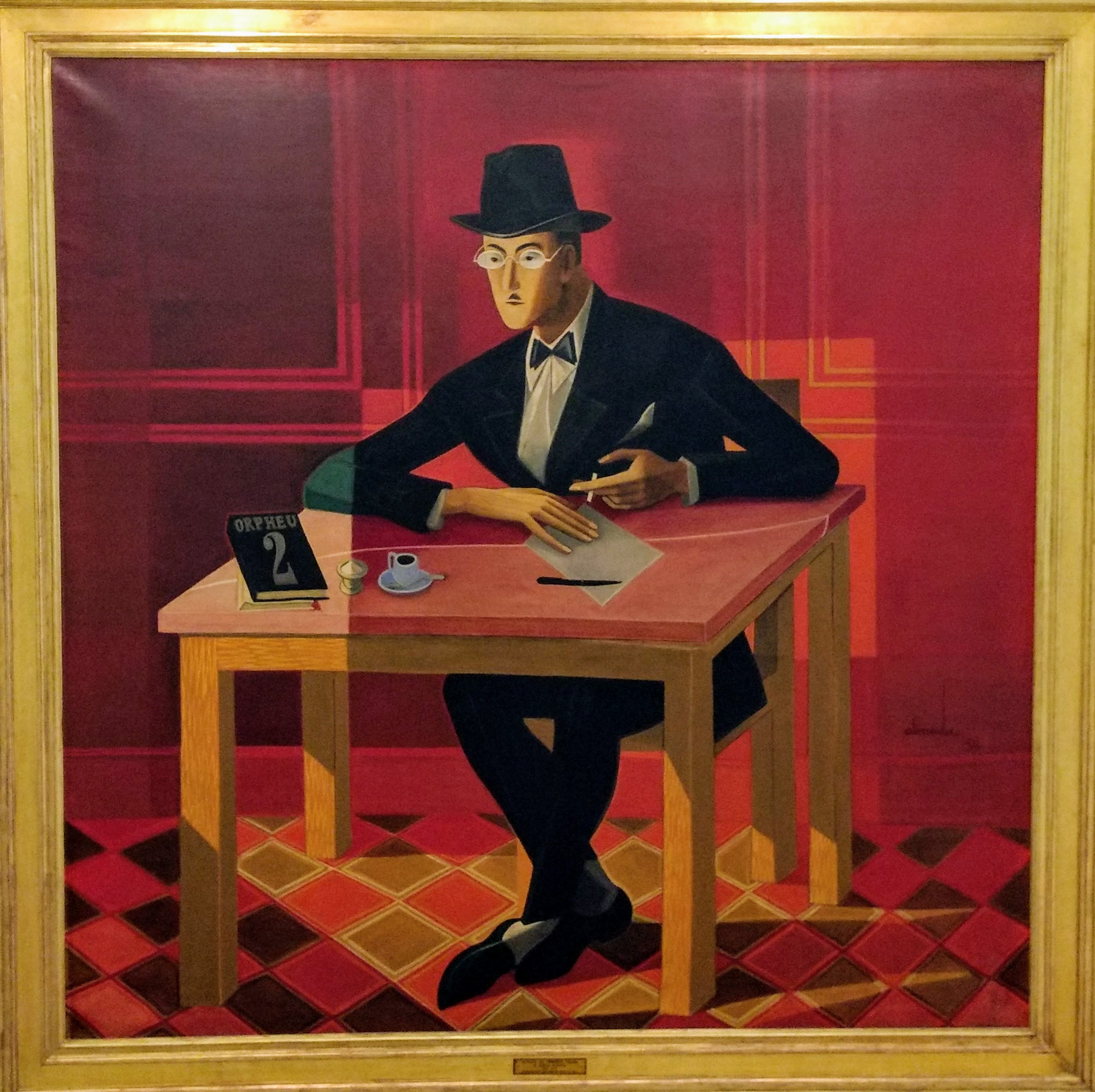

Fernando Pessoa was a poet, critic, translator, and publisher who was born in 1888 in Lisbon. He and his mother moved to South Africa when he was a boy, but at 17 he returned to Lisbon where he lived until his death at the age of 47. In Lisbon, he worked as a bookkeeper and lived in one room. He didn’t have friends or lovers. Instead, he wrote.

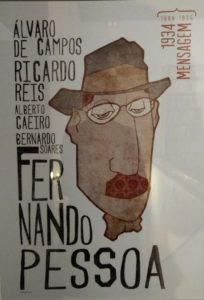

Pessoa did write under his own name, but more often he wrote under what he called heteronyms, which are characters — with detailed lives and backstories — he created to write under. It’s not clear how many heteronyms Pessoa came up with, but most of what I’ve read indicates he created upwards of 80 (maybe more).

In Lisbon, I find Pessoa everywhere. His face hangs on the wall at the Museu Nacional do Azulejo (Tile Museum). There are two statues of the writer in two different squares. I even see signs of him outside of the capital, when I spot a poster of him up in Obidos, at a literary-themed hotel.

But even more than literal representations of the writer, his spirit is what remains in Lisbon, casting a mist of creative intellectualism over the city. You feel his presence when you stop for a coffee at a sidewalk café or when you wander aimlessly through the winding, steep streets of Baixa and Chiado, passing tiny bookstores that have his titles displayed in their windows. Pessoa was a flâneur, but he stayed close to his beloved Lisbon for most of his adult life, and as I walk these same streets, I feel the ghosts of his footsteps beneath mine.

In The Book of Disquiet, he brings to life the world of Lisbon at the start of the 20th Century in the opening passage: “Installed on the upper floors of certain respectable taverns in Lisbon can be found a small number of restaurants or eating places, which have the stolid, homely look of those restaurants you see in towns that lack even a train station. Among the clientele of such places, which are rarely busy except on Sundays, one is as likely to encounter the eccentric as the non descriptor, to find people who are but a series of marginal notes in the book of life.”

In restaurants today I see these same people, drinking coffee, drinking wine, as if I’ve stepped back in time, and I can’t help but feel that his writing gives validation to the people left in the margins. There is comfort in a shared state of disconnection.

The Book of Disquiet, a book the author called “a factless autobiography,” is unlike any other book I’ve read before. Written under the heteronym, Bernardo Soares (though the editors of my edition assert that we should read it “as it evolved,” chronologically, with the earlier texts being attributed to Vincente Guedes, another heteronym), it wasn’t finished when Pessoa died, and as a result the text is fragmentary. This makes it a challenge for translators and editors to know how to order the hundreds of entries; different editors have different opinions on their approach, and this makes the various editions quite different.

It also makes the book difficult to categorize and hard to know how to read. It doesn’t have a clear narrative arc to pull the reader through, and it’s the type of book that gets exhausting to read after even a few pages. It’s sort of a writer’s sketchbook, a meditation on love, life, death, anguish, art, writing, solitude, loneliness, dreams, reality. It’s funny and sad, depressing yet still full of hope. It’s both ordinary and extraordinary. It seems to provide all of the answers, but at the same time only asks questions.

But still, as I read, it entices me. It gets under my skin. I find myself skimming a few pages only to be pulled in and start highlighting every word because every word feels like a part of me.

The woman at the Casa Fernando Pessoa assures me that there isn’t a correct way to read The Book of Disquiet. “It’s the type of book where you can just open it to any page, and you’ll find exactly what you need,” she reassures me.

That isn’t an easy way to read when one is stuck reading on a Kindle, but I imagine I’ll be buying a nice hardcopy for when I’m back in the States (the woman at CFP suggested the Penguin edition for those who might be interested).

As a writer, it’s interesting that the book was never finished, in spite of the fact that Pessoa spent decades working on it. The woman at the CFP was confident that the writer would have tried to publish it in his lifetime, but while reading I have been struck by the comments on imperfection in art. In the Book of Disquiet, Soares asserts, “We worship perfection, because we cannot have it; and we would loathe it if we did. Perfection is inhuman, because to be human is to be imperfect.”

A part of my wonders if this contemplation of perfection, something I struggle with myself as an artist, would make it impossible to complete a work like this. And yet at the same time, its imperfection is what makes it so hopeful, and so human, in the first place. When Pessoa died in 1935, the manuscript was found in two trunks in his one-room flat, just scraps of paper with no indication of how they should be ordered.

In writing classes, I always tell my students that form and content are the same thing; in essence, the way something appears on the page creates its meaning. So when we have a text whose form is formlessness, where does the meaning come from? In some ways, given what I know about this complex genius, I appreciate that he left behind a deconstructed pile rather than a polished piece (how very high modern of him).

In many ways Fernando Pessoa lived his life as a recluse, but through his creations he wasn’t alone. And in discovering him, I am reassured that I am not alone. In discovering him I have found a friend. A brother. A wanderer and dreamer. I have found exactly what I need.

How interesting! When I was in college, bathed in postmodernism and deconstruction, I would have LOVED this. (Of course, I was an English major, so we didn’t really focus on works in translation, but…)

He is very interesting — I think he makes a good book to put on one’s nightstand to read a few pages of each night. It would take ages to finish, but it would be a good comfort to keep with you for the long haul. I’ll let you read some passages when I see you in a few weeks. (I like to work that I’m going to see you in a few weeks in every response 😉 )

Just seeing this now, and it’s even fewer weeks now! 🙂

I know — can you believe it? I’m excited for you 🙂