Nina wants to stop for a drink, though it is only 9:47 a.m., and we’re only a few steps away from Tottenham Court Road tube station, our starting point; we’re only a few steps into our long day of flânerie. But as it is only 9:47, Erica and I reckon we’d benefit from an extra shot of caffeine and a final wee, and so we dash into a Costa Coffee for a quick pick me up.

Nina is six. She is Erica’s daughter, and she is my favorite flâneuse-in-training. The three of us are about to embark on a literary trek around London, focusing on Bloomsbury, the locale of the early 20th century informal society, the Bloomsbury Group, a group of writers, artists, and philosophers who were united in their beliefs about the importance of the arts.

Our journey involves a lot of wandering around pleasant streets and picturesque squares, Erica and I on foot, Nina on her kick scooter, and staring at buildings, searching for the blue plaques that indicate that various writers once lived and wrote there. We visit the University of London Senate House, the building that inspired the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell’s 1984. We have lunch at the 18th Century Lamb Pub where the Bloomsbury Group used to meet. We visit the Peter Pan statue at the Great Ormond Street Hospital, where JM Barrie gave the copyright of Peter Pan in 1937.

Mostly, though, I’m hoping to capture the spirit of Virginia Woolf, one of the core members of the Bloomsbury Group — along with her sister, Vanessa Bell, and her husband, Leonard Woolf. Maybe if I can find her, I’ll start to get her.

I’ve always had a bit of an odd relationship with Virginia Woolf. In graduate school, my friend Pat had a picture of an angel in her house, and we’d brainstorm different ways to kill her. I knew that I had my own angels that needed killing, and I thought if I started understanding Woolf, I could figure out how to capture them. I remember enjoying A Room of One’s Own, and I even liked Orlando. But my appreciation of her ended there. I struggled with her never-ending sentences, with the sheer density of her prose; I struggled with her stream-of-consciousness, with her leaps in thoughts and feelings. For the most part, Virginia Woolf was a source of bafflement in my literary and academic life.

Funny thing, though, I never stopped wanting to enjoy her. Unlike some other writers (cough, cough, Jane Austen) who I can appreciate intellectually but never care much to become an aficionado of (sorry gals, I do not get the Mr. Darcy love) I’ve always wanted to love Virginia Woolf. Stylistically, my writing is about as far from hers as one can get. But at my core, I’ve always intuitively known she’s a kindred spirit.

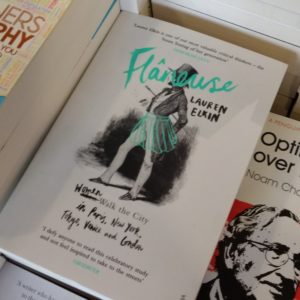

Lauren Elkin helped me fall in love with Virginia Woolf by helping me discover what now seems so obvious: Woolf is the ultimate flâneuse. For flânerie is not just a wandering of the body, but it is also a wandering of the mind, and both of these things are mirrored in Woolf’s work.

Virginia Woolf knew the power of being able to walk freely and anonymously through the streets of London, and her walking gave her material for her work. Woolf’s London, a London she explored on foot, and more specifically, her Bloomsbury, was a place of liberation, a place to help her escape the Victorian conventions of her upbringing.

While staying in Bloomsbury last December, I walked in a snowstorm from my bedsit (where for two days I imagined myself a 1920s single woman living in London) to Tavistock Square, where Virginia Woolf lived from 1924-1939. At the base of an unfortunate bust of the author, her eyes bulging as if in terror, her skin pocked, is a plaque honoring her with a quote: “Then one day walking round Tavistock Square, I made up, as I sometimes make up my books, To the Lighthouse; in a great, apparently involuntary, rush.”

I stood in front of her unfortunate bust, in the same square where Ms. Woolf stood, no doubt, thousands of times, the square where she lived and wrote most of her novels, clutching my umbrella as the snow buzzed around my face. In that moment something clicked, and her work became instantly accessible. Yes, sometimes I still have to spend an hour and a half unpacking a sentence, but this isn’t something I loathe anymore; it’s something I celebrate (note: this is one of the problems with reading on a Kindle. Woolf is not meant to be read electronically; she is meant to be read with a luxurious and rambling touch, your fingers whispering across soft pages as you underline words and phrases, flipping back to previous passages, dog-earring corner after corner).

In her book, Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit talks about the relationship between reading and walking and how the storyteller guides the reader through the landscape of the story. She states: “To write is to carve a new path through the terrain of the imagination, or to point out new features on a familiar route. To read is to travel through that terrain with the author as guide—a guide one may not always agree with or trust, but who can at least be counted upon to take one somewhere.” A story, like a road, is a route through the past, through someone’s past, through a place, through a lifetime, and to follow it is to immerse oneself in that past. Reading Woolf is like walking the streets of early 20th century London, a London that has, in some ways, vanished today but is available to us in her oeuvre.

Woolf takes on the role of guide both literal and metaphoric in her essay about wandering through London, “Street Haunting,” under the guise of a quest for a lead pencil. She leads the reader through the streets of London for a contemplative, evening stroll. Yet the pencil is the narrator’s mere excuse, and it’s clear that she finds respite in the city streets. Woolf writes, “So when the desire comes upon us to go street rambling the pencil does for a pretext, and getting up we say: ‘Really I must buy a pencil,’ as if under cover of this excuse we could indulge safely in the greatest pleasure of town life in winter—rambling the streets of London.”

She emphasizes that the setting must be at dusk in winter, “for in winter the champagne brightness of the air and the sociability of the streets are grateful.” The twilight London streets provide the anonymity she craves as they provide her the opportunity to merge freely into the crowd to observe, and through her observations she enters the lives of strangers. It is at this time that “we shed the self our friends know us by and become part of that vast republican army of anonymous trampers, whose society is so agreeable after the solitude of one’s own room.”

Flânerie finds its way into Virginia Woolf’s fiction, perhaps most notably in Mrs. Dalloway, a novella that takes place over the course of just one day. Location — more specifically, post-World War I London — plays a central role in the novella, not just in terms of establishing the where and when of setting (though it is hard to imagine this story taking place anywhere but 1920s London) but in terms of creating the story’s structure itself. Characters walk, often in solitude, often immersed in their own thoughts, for pages at a time, and it is through the movement of walking that Woolf’s story finds its form.

In fact, “walk” in some form appears 63 times in Mrs. Dalloway. For a book that’s only 63,000 words long, that’s a lot of walk-ing. The novella begins with the declaration: “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” With that, the character’s — and the story’s — movement commences: “What a lark! What a plunge! For so it had always seemed to her, when, with a little squeak of the hinges, which she could hear now, she had burst open the French windows and plunged at Bourton into the open air.”

I decided that if I’m going to understand books written by a flâneuse about people who literally walk their way across the pages, I needed to hit the streets of London myself and, again, literally follow in the footsteps of Virginia Woolf. Using an online tool to create a plan, I plotted out their paths and spent three days walking the footsteps of each of the main characters in Mrs. Dalloway: Mrs. Dalloway from her Westminster home through the St. James and Green Parks to Old Bond Street, where she famously buys the flowers and hears the car backfire; Septimus and Rezia, from their witnessing the car backfiring to their walk though Regent’s Park and down to Septimus’s appointment with Dr. Bradshaw; and Peter’s walk also through Regent’s Park, on his way to his hotel after stopping by Mrs. Dalloway’s home.

While each of the characters has a specific destination in mind, theirs are not linear journeys in any way. Their walking is that of the flâneur/flâneuse. In the story, walking serves as a means of physical movement to get from Point A to Point B, but it is also a means of mental movement, a means for contemplation; walking becomes the catalyst to a wandering from present to past and back to present again; as the characters meander through London, the narration meanders with them.

Walking also creates connections between the otherwise-disconnected characters’ lives: Mrs. Dalloway and Septimus/Rezia are linked when they witness the motor car’s backfire near Mulberry’s flower shop; Septimus and Peter are linked when Septimus sees Peter at Regent’s Park and mistakes him for Evans, his comrade who died in the war; Septimus and Elizabeth Dalloway are later linked when, from his apartment window, he sees her omnibus pass by on Fleet Street. These connections allow for the narration to fluidly shift from one character to the next, to guide the story to its next location, and to weave the threads of their stories together.

As I start my own journey, Big Ben is still there to strike the hour, though when I return in autumn and winter it is covered with scaffolding, and Victoria Street is still there to cross, albeit perhaps a bit blander than in Ms. Woolf’s day). As I weave around hordes of tourists, I am a bit disheartened that London today would in some ways be unrecognizable to Mrs. Dalloway (and by extension, to Virginia Woolf). For Clarissa Dalloway, “Bond Street fascinated her; Bond Street early in the morning in the season; its flags flying; its shops; no splash; no glitter…salmon on an iceblock.”

Gone today is the simplicity of fish on ice, a 50-year-old shop selling tweed. Today’s Bond Street, a retail mecca in London, has been overrun with shiny chain stores and high end designers: Victoria’s Secret, Zara, and Jo Malone; Tiffany’s, Gucci, and Alexander McQueen. It has been overrun with both “splash” and “glitter.” There is a sign for Mulberry’s, the name of flower shop that Mrs. Dalloway goes to, but today it is a store that sells leather goods. As enjoyable as the day is, I have to admit that it’s a bit disappointing.

It’s interesting to think about a woman like Woolf, whose true love was London, whose life and craft was so immersed in the city. She read London with her feet and her eyes, and she brought what she read on those streets to her writing. Learning to read London has helped me to learn to read Virginia Woolf and vice versa. But Woolf’s London doesn’t exist anymore outside the work she left behind. In thinking about how an artist develops a relationship with a place, I wonder how much of that relationship hinges on the time of a place. How much of a place exists only in a specific moment? When a place changes, how much does our relationship with that place change? What makes someone fall out of love with a place?

While walking in the footsteps of Clarissa Dalloway, Septimus & Rezia, and Peter helped me to read London, I wonder if it’s Woolf’s London that I’ve internalized or instead the London of today. I wonder whether or not Virginia Woolf would still be able to find the “champagne brightness” in an air polluted by the endless ding of cell phones.

In a speech to her Memoir Club, Virginia Woolf asked, “Where does Bloomsbury end? What is Bloomsbury?” We can think about the geographical answers to these questions — a square, an address, a street — but I think about the answers more philosophically. Elkin reminds us that, “For Woolf, Bloomsbury was not only a geographical neighbourhood but an abstract entity, an idea about creativity and bohemianism and an idea about freedom.” In that sense, Bloomsbury was a place, but a place in the mind as much as a physical place. Bloomsbury of the early 1900s may not exist as a concrete entity, but its spirit remains. Perhaps in that regard Bloomsbury never really ends. Perhaps we free spirits simply carry it with us to the next location we decide to explore.

As usual, your writing has excited me and stimulated memories of our time together in London in October. I especially think of Regent’s Park and looking for the flower shop. Bravo! Well done!

I’m glad we got to go there together — that was such a lovely walk on a lovely day!

I like your take on the “It isn’t what it was” problem — after all, no place is what it was, but it’s always something to the next person to get there, and while you might not get from Woolf’s streets what she got from them, you’ve clearly gotten something. As you do from everywhere you wander. 🙂

I think that’s one of the things I’ve been thinking most about these past few months — often we go to a place thinking it will be what it WAS (whether from a book we’ve read, a movie we’ve watched, a painting we’ve seen, or even a previous trip we’ve taken) when in fact what WAS no longer exists. I know that I tend to idealize these previous forms, but the danger is that it can lead to disappointment when my expectations aren’t met.

I experience that expectation/disappointment reality when I return to Detroit—not just to the House where I lived for most of my early years, but in the neighborhood and entire city.

Yet going back has become necessary and creates a new, separate reality.