I must write. If I stop writing my life will have been an abject failure. It is that already to other people. But it could be an abject failure to myself. I will not have charmed death — Jean Rhys

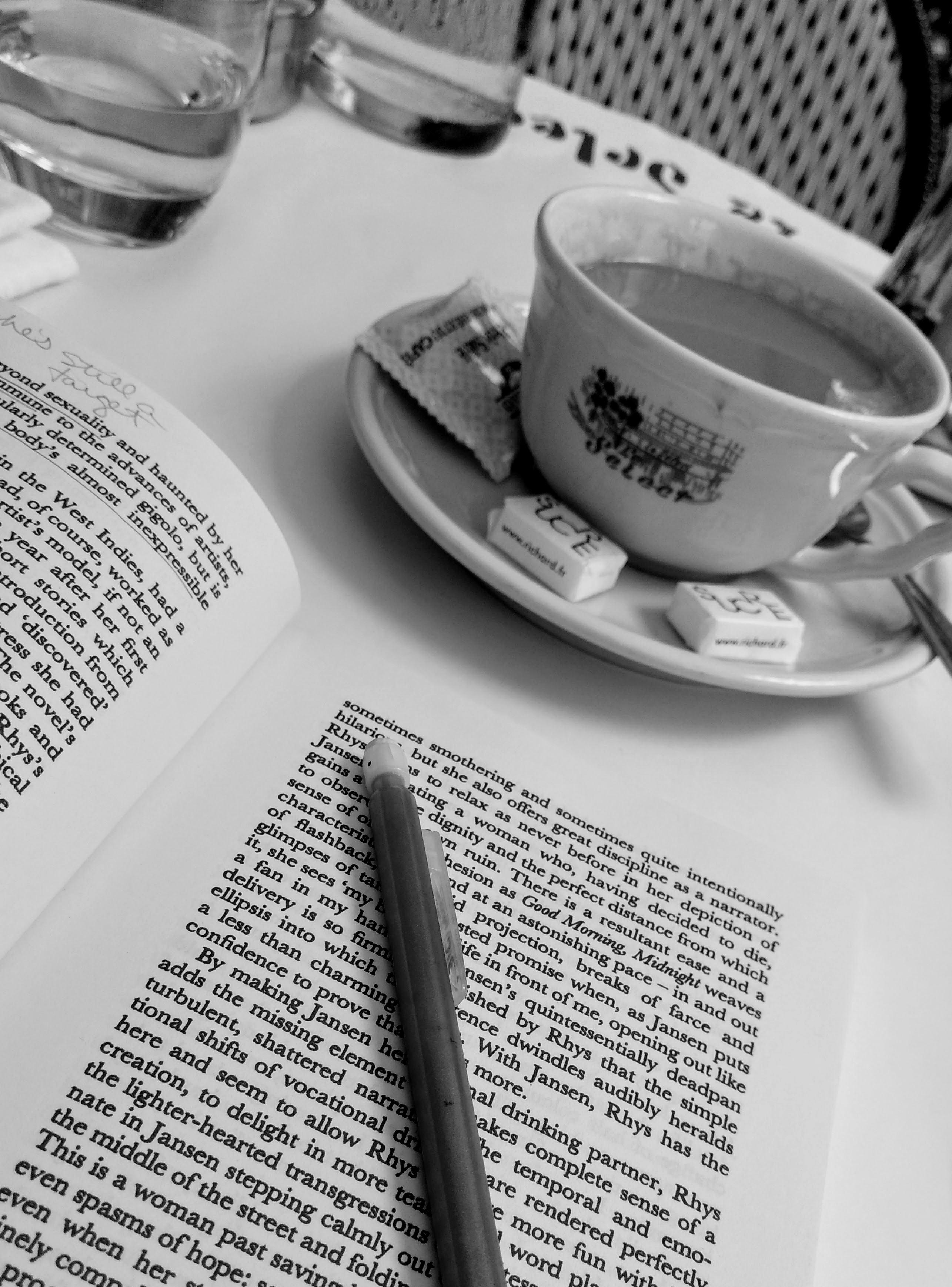

I am sitting in my fourth café of the day because I am in Montparnasse and I feel I owe it to the memory of Jean Rhys to pretend like I’m in one of her novels. So, like a Rhys protagonist, I carefully choose the places where I know I’ll be welcome, and then I have just one apéritif at a time before moving on to the next spot (though unlike a Rhys protagonist, I realize I owe it to my liver to stop after number four).

I started at Le Select five hours ago because the (almost always) friendly waiters, perhaps amused by my broken French, smile in recognition when I sit down and because they bring me a steaming pot of coffee next to a steaming pot of milk, and I can linger over the luxuriousness of something so simple, though today I feel the chill of the season’s turn on my stockingless feet and I’m wishing I had chosen to sit inside instead of outside for a change.

But outside feels more like Paris, and as I sit at my table, a light drizzle stirring in the air, I make notes in my journal and watch as Parisians and tourists pass by on Boulevard du Montparnasse, bareheaded or clutching a rainbow of umbrellas. Though even those without umbrellas don’t seem bothered by the rain.

Of course, Montparnasse, while not being as much of a tourist destination as other neighborhoods in Paris, is famed for its literary and artistic history. The big cafés, some of the most famous cafés in the world — Le Select, La Coupole, La Dôme, La Rotonde, La Closerie des Lilas — still stand strong, and while lunching at La Coupole I find myself checking over my shoulders to see if Simone de Beauvoir or Jean Paul Sartre has slipped through the door for a Pernod in the afternoon. On virtually every street I roam I come across plaques with names of artists, writers, and composers, but I have yet to find a plaque to remind the world that Jean Rhys once wrote there. Her books are hard to come by even in Paris. and I wind up ordering two online and having a friend bring them to me when she comes for a visit.

In her essay, “Left Bank Apértifs of Jean Rhys and Ernest Hemingway” Irene Thompson compares the parallels between the two writers’ works — namely that both received similar early praise for their literary style and subject matter — and then considers why one remained visible (Hemingway) and the other became nearly invisible (Rhys). In fact, while Hemingway was winning the Nobel Prize, Rhys moved to a place of such obscurity for two decades that nobody knew where she was until a BBC production of Good Morning, Midnight brought her out of hiding — after which she published her most well-known book, Wide Sargasso Sea (the only book of hers I’d ever previously read). Thompson questions: “[W]hy were so many women writers lost in the first place?…Just as female characters have been trivialized and subordinated in their appearances in books written by many males, so have too many ‘real’ women as authors been buried.” Why is Rhys’s work near forgotten (relegated to the shelves of “women’s writing”) and Hemingway’s considered mandatory reading in the canon?

Walking the streets of Paris, I see Hemingway’s name everywhere, while Rhys’s lies in the city’s shadows. I’m not trying to undermine Hemingway’s work. In my own life, he has been one of my greatest influences; I’ve long said that The Sun Also Rises is one of the reasons I became a writer, and I eagerly enrolled in a Hemingway-Faulkner class my first semester in graduate school. But I’m trying to imagine the impact Jean Rhys’s writing would have had on my life as a writer had I been able to enroll in a class where we examined her body of work instead of his.

Hemingway, as the legend goes, was master of this land. But Jean Rhys was here, too. Not that I necessarily think Rhys would be concerned that she isn’t included in the (mostly) boys’ club. Lauren Elkin reminds us in Flâneuse that “Rhys was not part of the expatriate scene in Paris” and that she was fine with that. At Shakespeare & Co., the few books of hers I find aren’t even shelved in the “Lost Generation” section (though there is a drawing of her on the wall). I think she’d be okay with that, too. Elkin quotes a 1964 letter Rhys wrote to Diana Athill: “The Paris all these people write about, Henry Miller even Hemingway etc. was not ‘Paris’ at all — it was ‘America in Paris’ or ‘England in Paris.’ The real Paris had nothing to do with that Lot.” So while Rhys may have rejected the expat vision of Paris, she still embraced the city’s underbelly found in its dark corners.

Rhys’s work tackles these same questions about existing on the outskirts. Rhys’s characters, like Rhys herself, seem intuitively drawn to the seedy side of Paris, to the real Paris. Like it or not, they are “always wanting to be different from other people” as protagonist Sasha Jansen shamefully observes in a luminal-induced dream in Good Morning, Midnight. They are women who drink and who, more often than not, drink to get drunk. This behavior, for a woman, is a source of social condemnation as Julia’s landlady notes in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie: “[S]he disapproved of Julia’s habit of coming home at night accompanied by a bottle. A man, yes; a bottle, no.” For the characters, drinking is a means of escape from their suffering, yes, but it is also a source of “luck” as Sasha puts it. More specifically, as the narrator observes in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, “When you were drunk you could imagine that [the river] was the sea.” Drinking helps maintain the possibility of hope in an otherwise hopeless life, even if the only hope it provides is coming up with the “bright idea of drinking myself to death” as Sasha early on articulates.

The women in Rhys’s stories, poor and scarred by past and present tragedy, cling to whatever means they find (usually money from men) for their survival. But they are bound by the rules of society, and ultimately they simply do not — or rather, cannot — fit in. They remain visible, they are not-yet forgotten, but they stand out for all the wrong reasons; they stand out because they cannot figure out how to speak, behave, or even simply exist in the right way. Perhaps my love for Rhys stems from her refusal to sentimentalize anything or to romanticize her characters. True, her characters make some dreadful decisions along the way, though then again, what alternatives are there? She didn’t claim to be for women’s liberation, yet reading these stories in the context of a patriarchal world, to me they are utterly feminist.

At the foundation of flânerie is the ability to move through the world invisibly. And walking in Paris (or London), as Lauren Elkin writes about in Flâneuse, is central to the lives of Rhys’s characters. But Rhys’s stories show that even in a city like Paris, women cannot escape being visible when they are in public, nor can they escape the judgment that follows (and the inevitable self-loathing that follows that) especially when they break society’s rules, when they fail at playing the game. This judgment intensifies with age. At this point, any last hope for fitting in starts to crumble. In Good Morning, Midnight, Sasha (in her 40s she’s the oldest of Rhys’s protagonists) has returned to Paris, in “need [of] a change,” as a London friend says to her. Yet as Sasha walks the familiar streets of Paris, plagued by the cruelty of the world, she is haunted by memories of her past life there — a past marred by degrading jobs, harassment, a broken marriage, death, grief. As her story slips back and forth from memory to present, she recognizes that every place she goes is “saturated with the past.” Similarly, for Julia, in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, walking becomes a source of alienation. She quickly shifts from feeling “exultant and youthful” to worrying that “she must look idiotic, walking about aimlessly” when she gets lost walking in London. She later expresses, “I hate drifting about streets…It makes me awfully miserable.” While there is the clear potential for freedom in walking, in the end she comes to loathe it.

Then again, while out in public, there’s always the risk of being stopped by strangers who want to know, “Pourquoi êtes-vous triste?” Why are you sad? two Russians stop to ask Sasha on Boulevard St. Michel. (Interestingly, Marya in Quartet gets asked the same exact question; perhaps this is the early 20th century way of telling women to smile?) Walking comes with the fear of being judged, the fear of being accosted, the fear of being seen. No wonder Julia finds it so miserable. Women cannot simply exist on their own terms, whatever those terms may be.

Along with ghosts from the past, Sasha is haunted by the woman she has become. At a restaurant Sasha overhears a man say to his companion: “Tu la connais, la vielle?” Do you know the old woman? Sasha’s reaction is, at first, utter shock: “Now, who is he talking about? Me? Impossible. Me — la vielle?…This is as I thought and worse than I thought….A mad old Englishwoman, wandering around Montparnasse.” Sasha’s slow realization is horrifying to her. For worse than being alone, worse than being female, is being in public, a female, alone, and old. (How dare she?) Later, Sasha is confronted by an acquaintance from her past who questions, “Qu’est-ce qu’elle fait ici?” What is she doing here? Sasha combines the two observations into one, a sentiment that runs throughout the rest of the novel: “Qu’est-ce qu’elle fait ici, la vielle? What the devil (translating it politely) is she doing here, that old woman? What is she doing here, the stranger, the alien, the old one?” A woman — especially an aging women — is a foreigner, an outsider, one that ultimately doesn’t belong. Sasha is hyperaware that her presence is a source of ridicule, and she wants nothing more than to blend in, to be a “respectable woman.”

For Sasha, even familiar mirrors become reminders of her age and a reminder of who she used to be and who she has become. When visiting a familiar lavatory, the mirror speaks to her: ‘Well, well,’ it says, “last time you were in here you were a bit different, weren’t you? Would you believe me that, of all the faces I see, I remember each one, that I keep a ghost to throw back at each one — lightly, like an echo — when it looks into me again?’ The mirror becomes an artifact to remind her of what she once was and what she has become.

Aging isn’t something that only the middle-aged have to deal with. It is a thread that runs throughout Rhys’s work; even 24-year-old Mayra in Quartet has “dread that she was getting old.” Similarly, Julia, in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, who is constantly reminded — both by others and by herself — of how much she has aged, observes while waiting for a show to start that “[t]he girls were perky and pretty, but it was strange how many of the older women looked drab and hopeless, with timid, hunted expressions. They looked ashamed of themselves, as if they were begging the world in general not to notice that they were women or to hold it against them.” There is a sense of shame in the older women and a feeling of desperation in not wanting the world’s eyes to land on them; they feel that they are being “hunted” by onlookers and fear being mocked for no longer being the “perky and pretty” girls beside them. The older women are aware that there is a punishment for aging and that they would rather their womanhood become invisible than receive that punishment.

I can relate to this, as a middle-aged woman, a woman who hasn’t accomplished any of the things that, at least historically, have defined someone as a woman: motherhood, marriage, domesticity. I may not have suffered the same traumas that Sasha has suffered, but as I wander the streets of Paris alone, I can’t help but wonder if I still belong here, what the eyes that land on me say. I question: Will the right haircut keep me young? A fresh hair color? Does this new outfit make me youthful? Or does it scream, “I am an old hag pretending to be young?” Is it too late for me? Catching my reflection in the mirror, I sometimes stop and say, “Is that what I look like now? Is that really me?” My own ghosts in the mirror echo back to me an unlined face, shinier hair, smoother skin.

Women today, just like the women in Rhys’s novels, often carry the idea that the right hairstyle, the right shoes, the right outfit, will alleviate their suffering, and that suffering, for so many women, is often rooted not just in their experiences but in the realities of getting older. Because in a world that celebrates youth, what happens when a woman becomes la vielle? Does she, too, become “drab and hopeless”? “Ashamed”? In Good Morning, Midnight, Sasha clings to the idea of dyeing her hair much “as you hang onto something when you drown.” The idea is rooted in desperation; Sasha has a sense that this small act will somehow save her, that this is the last chance she has in life. The hair — and later on, the hat, the dress — will aid her with “the transformation act.” She must disguise who she has become as a means to belong. Shopping helps her “feel saner and happier.” At least temporarily.

Today, as women get older they tend to just vanish (metaphorically, that is). They simply fall off the radar of the patriarchal gaze, and in those rare moments when they are seen, they are often subject to extreme scrutiny and ridicule. An older woman is only attractive if she manages to maintain a youthful appearance, to not let herself go. Interestingly, many of my older female friends tell me that this newfound invisibility has been a source of liberation; they can find their value in things beyond the patriarchy’s narrow parameters. (Watch Amy Schumer’s Last F**kable Day for a damn funny glimpse at this phenomena.) But, as I find myself receiving fewer glances, fewer suitors, less attention, I must admit that I struggle with this, that I have a lot of fear not necessarily of becoming older, but rather older and invisible. Ironic because I know I’m a far-more interesting and attractive person today than I was in my 20s. But even so, as a single, childless, never-been married woman in my mid 40s, I would be lying if I claimed it didn’t leave me frustrated or make me feel like dying alone is inevitable. Like Sasha, like Julia, I struggle over the possibility that perhaps I have passed my last chance for love.

Just a few days ago, while having a pint at a pub I frequent for weekday happy hour, I met a much-younger French man, a man with hopeful eyes and a crooked grin. We piece together a conversation of fragmented French and English, and although I sense that he understands me as little as I understand him, the conversation overall flows.

We talk for three hours, the lazy happy hour shift transforming into the wild weekenders. He is surprised that I’m living alone in Paris; he is shocked but intrigued that I’m not married, that I don’t have children. But he tells me that he likes older women, that he admires my independence and my intelligence. He says that I’m beautiful, I have beautiful eyes, I have a beautiful body, but he seems concerned that if I wait much longer, my life will be gâchis, a mess. Perhaps it’s the beer, but I suddenly feel like I’ve just stepped into one of Jean Rhys’s novels — a tipsy middle-aged woman flirting with a younger man. Is this it? Is this my last chance at love? And no matter what I say to him, no matter what language I use, I cannot convince him that I’m happy alone, that I would prefer being alone if I can’t find a man who’s my equal. (In truth, I want to tell him that my uterus is in the medical waste bin behind the San Francisco Kaiser, that my life is probably already gâchis, but my French lessons stopped before we got to gynecology.) By the time we are ready to leave, the pub is crowded and outside the rain has started to fall. He walks me back to my apartment, and in that moment it feels good to just be talking to someone. Though I know — and I think even those hopeful eyes know — he is not the one to pull me from this mess. As he walks away, clutching a rain-soaked scrap of paper with my email address on it, I realize, I made this beautiful mess, it belongs to me, and it’s up to me to decide if I want to clean it up or just live with it.

I love your writings and want to read Jean Rhys, although I may have read WIDE SARGASSO SEA. (Does becoming la vielle need to play with my memory as well as my appearance?)

Thanks, Mumsie! I have three of her books here that I’m giving to you to take back with you (well, one is in French). So you can read them before you mail them back to CA 🙂

You have captured exactly how I feel. All the time. Like I’m invisible. And have made me decide to read Jean Rhys. Thank you.

Thanks, Hannah!

Sometimes I don’t know what’s worse — invisibility or visibility with judgment. That’s the struggle. Jean Rhys is just amazing in so many ways. You’ll love her.

Words cannot express how much I love this one. (Well, someone’s words probably could, but not mine, not right at the moment.) Beautifully written and thought out.

Thanks! I could write for days about Jean Rhys. She’s just. Yes. Words can’t express it!

Can’t wait to read her now!!

I want to hear what you think — I sense you’ll love her!