Once upon a time I paid a visit to Jim Morrison. It was early January, 2000, and a friend and I had traveled to Paris for the New Year. We made our faithful pilgrimage to Cimètiere du Père Lachaise and predictably got lost in the labyrinth of tombstones until we finally stumbled upon a flock of tourists huddled around Morrison’s grave. We joined them, and as we all stood there in the cold, a young man with long hair and an open trench coat sauntered past us, got down on his hands and knees in front of Jim’s tombstone, kissed the earth, then swiped a cigarette someone had left behind. He jumped up and, tucking the cigarette behind one ear, strode off, just as smooth as he had arrived. As the man walked away, he said in an American accent without a hint of irony: “Morning, tourists.”

It was simultaneously the coolest and the most annoying thing I had ever seen. I didn’t know if I should punch the guy, or marry him.

In the most-visited cemetery in the world, Jim Morrison’s grave sees so much traffic that today there is constant security to monitor fans’ behavior; people have been caught doing drugs or having sex on his grave. But Jim Morrison is not the only resident of Père Lachaise, and Père Lachaise is not the only cemetery of note in Paris, and so in honor of Halloween I decide to take a walking tour of the three biggest cemeteries in the city: Cimètiere de Montmartre (officially known as Cimètiere du Nord), Père Lachaise, and Cimètiere du Montparnasse. In addition to being the final stop for hundreds of thousands of guests, these cemeteries are just interesting places to explore. Many plots are simple headstones, some crumbling to the point of non-recognition, but you’ll also find yourself wandering between elaborate, ornate monuments and mini-mausoleums. And even though millions of people visit Paris’s cemeteries each year, for the most part they are large enough spaces that you can experience peaceful solitude.

Stop one is Cimètiere de Montmartre. After a chaotic metro ride (story coming) my first accomplishment of the day is to not be able to figure out how to get inside. So I wind up walking around the entire perimeter of the cemetery before finding its sole entrance (at 11 hectares, that’s a pretty big diversion. It probably would have been wise to figure that out ahead of time — it’s on Avenue Rachel under Rue Caulaincourt, FYI). There’s a convenient laminated map at the entrance, which comes in handy during my visit. Opening in the early 19th century, Montmartre Cemetery was constructed at the site of an abandoned gypsum quarry. Today it’s home to many famous artists, and I make a quick lap (this time around the inside) to visit writer Alexandre Dumas, fils, painter/sculptor Edgar Degas, and ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky (my favorite grave of the day — in spite of my hectic arrival, it makes coming here worth it).

Admittedly, my trip to Montmartre was more stressful than pleasurable, and after realizing that it’s a 3-mile walk to Père Lachaise, I wisely decide to take the metro again. The largest cemetery in Paris, Père Lachaise opened in 1804 and is built over 110 acres; its size and layout means that it can be an overwhelming place to navigate. It’s still in operation, though there are strict rules for who can be buried there — and with the recent practice of 30-year leases for its occupants, it seems there are also strict rules for who can stay! There are hundreds of famous residents here, and the landscape itself is so fascinating that it’d be easy to spend all day wandering its haphazard plots. But I don’t have much time to wander today. With one cemetery down and one to go and already knowing how difficult it can be to find who you’re looking for (speaking of: where the frak is Balzac?) I’ve arrived with a plan, a downloaded map, and a list of the locations of a few of my favorites to seek out. Of course, even with my careful strategy in hand, I anticipate multiple meanderings. While there are maps that lead visitors to specific plots, Père Lachaise is what I’d call chaotic order; the maps are mere guides, and it’s inevitable that you’ll spend some time maneuvering decaying graves.

Though, of course, that is the fun of it all. Sort of like playing “Where’s Waldo?” with tombstones instead of striped sweaters.

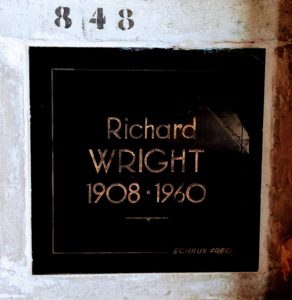

I’m happy to discover that Eugene Delacroix (he of my favorite painting in the Louvre) is buried here and that he has his own avenue (which almost always makes it easier to find someone — almost). After he and I have a small chat, I head up to the Columbarium. There are thousands of dead people here on multiple levels — both the cremains of people as well as cenotaphs to honor those whose remains are elsewhere. Even though things are clearly numbered, it still isn’t easy.

While trying to find Maria Callas I team up with a French woman and her son who are also looking for the opera singer. After we’ve been looking for several minutes, we realize there’s a whole additional level underground. On our way to the stairs, the woman says to me, “It’s strange, spending all of this time looking for a name carved into the wall.”

“It is strange,” I say, “though I have to admit I teared up when I finally found one of my favorite American authors, Richard Wright.”

She nods at me. She understands. Together we find Maria Callas.

I have to admit that it is sort of a baffling thing to do, slogging through the dirt, spending hours sorting through broken tombstones, searching for the names of people we’ve never even met. I suppose it’s like having an emotional reaction when a celebrity’s death enters our news feed; we don’t know them, not literally, but we know them through their œuvre, through their life’s work. Seeking them out at a cemetery is like seeking out a piece of who we are because of them and thanking them for what they’ve shared with us. While these graves are memorials for the dead, it’s clear that in many ways they serve to connect the dead to the living, whether the living is friend, family, lover, or distant admirer. Passing tombstones so overgrown with weeds and corroded to the point that there is no name visible, no date, no key to who once was, I am reminded that every grave represents a human being — or often multiple human beings — their graves a physical reminder of the connectivity linking the past to the present and the present to the future. Sometimes these connections leave tangible reminders — a book, a painting, a song — though more often the connections are intangible and never even known.

I leave the Columbarium and head over to say “hello” to Oscar Wilde, who died penniless and in exile in Paris in 1900. The flamboyant and witty writer’s grave, a flying naked angel, had been attracting so many admirers — in the form of lipstick kisses and graffiti that were permanently damaging the stone — that after multiple cleanings the tomb had to be closed and then reopened, protected by a glass barrier. Lines from Wilde’s poem, Ballad of Reading Gaol are inscribed on the grave: “And alien tears will fill for him / Pity’s long-broken urn, / For his mourners will be outcast men, / And outcasts always mourn.”

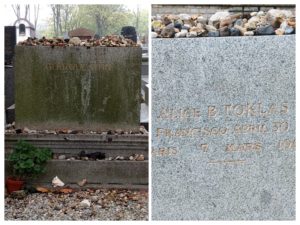

Leaving Mr. Wilde an invisible kiss, I stroll past the memorial garden with several monuments to World War II/the Holocaust before finding Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, who are buried together. As I’ve previously written, Gertrude Stein is remembered for being a supporter of many then-unknown artists and writers in the early part of the 20th century as well as for her own writing. The tombstone is simple, straightforward, solid, sort of like Gertrude Stein herself, and it’s covered in small stones. And fitting to the couple, Alice B. Toklas’s inscription is on the back of Gertrude Stein’s; just as she was in life, in death Alice stays in the shadow of Gertrude, though her eternal support is apparent.

I leave my own stones for the two women and offer my thanks. Without them, we wouldn’t likely have the modern era as we know it; many of the great artists and writers in our canon might have never been discovered. But more on that later.

It’s after 1 p.m., and I haven’t eaten anything in hours. And I still have to walk to Montparnasse. So after stopping by the graves of Édith Piaf, Modigliani, Pissaro, and (finally!) Molière — who I hadn’t been able to find with my friend, Erica, in August and was only able to find this visit with the help of two New Yorkers — I pop into one of the many cafés surrounding Père Lachaise for a fast lunch (translation: I shove bread and omelette into my mouth and wash it down with red wine) and then head back to the Left Bank.

Walking to Montparnasse from Père Lachaise is a fairly straight shot. Stroll along Rue de la Roquette until you get to the hectic Place de la Bastille and keep walking on Boulevard Henri IV, crossing Ìle Saint-Louis over to the Left Bank. Even passing through more residential neighborhoods, I am reminded of all of the dead people I have read. Of course, as I pass Bastille, I am reminded of the French Revolution and the art and literature throughout history that have centered on the site of the former fortress (hello, Victor Hugo!) After I cross the Seine, in the distance is Shakespeare & Company, full of both the dead and the living, and as I approach Luxembourg Garden I pass two plaques for James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway — almost directly across the street from each other, Joyce at 71 Rue Cardinal Lemoine (where he lived during the summer in 1921 and may have finished editing Ulysses) and Hemingway at 74 (where he lived from 1922 – early 1924 with his first wife, Hadley, in an apartment with no running water).

Finally, when I feel like I am about to become the walking dead, I arrive at my final destination (well, figuratively speaking). Cimetière du Montparnasse seems so organized and logical after being at Père Lachaise. Made from three farms in 1824, the cemetery is home to many famous artists, writers, and intellectuals — including Samuel Beckett, Serge Gainsbourg, Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, Charles Baudelaire. There seems to be a memorial starting when I arrive, so I don’t spend much time here, but I pay a visit to Duras, Sartre, and Beauvoir. For Marguerite Duras, whose grave is decorated with multiple plants, I leave behind a blue pen in a tree that holds dozens of pens and pencils. For Simone de Beauvoir I leave one of my favorite quotes of hers: “I tore myself away from the safe comfort of certainties through my love for truth – and truth rewarded me.”

Who would I be without their legacy?

I’m near collapse. My phone step counter indicates that I’ve walked almost 25,000 steps today (my feet are thanking me for taking the metro to Père Lachaise!) and the only thing that keeps me going is knowing that I have my choice of cafés in Montparnasse to get an aperitif. I choose Rotonde because Le Select would require turning left on Montparnasse Boulevard and walking an extra fifty steps; that’s how tired I am. I order a crisp glass of rosé, and the friendly waiter laughs when I immediately polish off the little bowls of olives and peanuts he brings me alongside my wine.

“Voulez vous plus?” he says when he gives me the check. Do I want more?

“Non, merci,” I say. No more. I’m happy the day is done.

What a day! My feet are happy I wasn’t with you, but my heart wishes I could have been.

Oh, we would have had so much fun together!

You make every adventure about which you write sound so exciting and I can feel like I’m there, with you . . . (Oh, I only wish . . .)

Thanks! Hard to believe you only left a week ago!

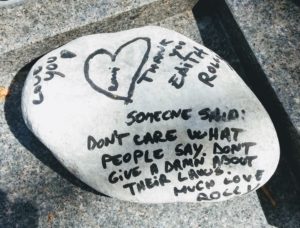

What a beautiful day that was! And you’re right how strange it is to be moved by plaques, but it’s the moment it creates — the small remembrance of that person — and I love how these moments are memorialized by pebbles, pens, and invisible kisses!

Thanks for the sweet comment. It’s funny, but I was finding myself wanting to memorialize things, whether through a comment or leaving a token. It felt nice, offering thanks to so many of my influences.